INTRODUCTION

One lazy winter afternoon, I wanted to pursue a new cross-stitch project and began to look for pattern ideas. Tired of clichéd Google search results, I casually prompted DALL-E1, an AI model for text-to-image generation, to visualise one unit of cross-stitch. Several tries later, I ended up with twelve distinct variations of cross-stitch. These images resembled one another, like a family portrait, individually distinct but sharing visual traits. I began referring to these image variations as Family Resemblances, inspired by the term coined by the late philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein2.

What lessons can a Wittgensteinian approach to new AI-generated images offer to designers and craft communities? How can it help us see and interact differently with large-scale image datasets containing historical craft patterns and designs?

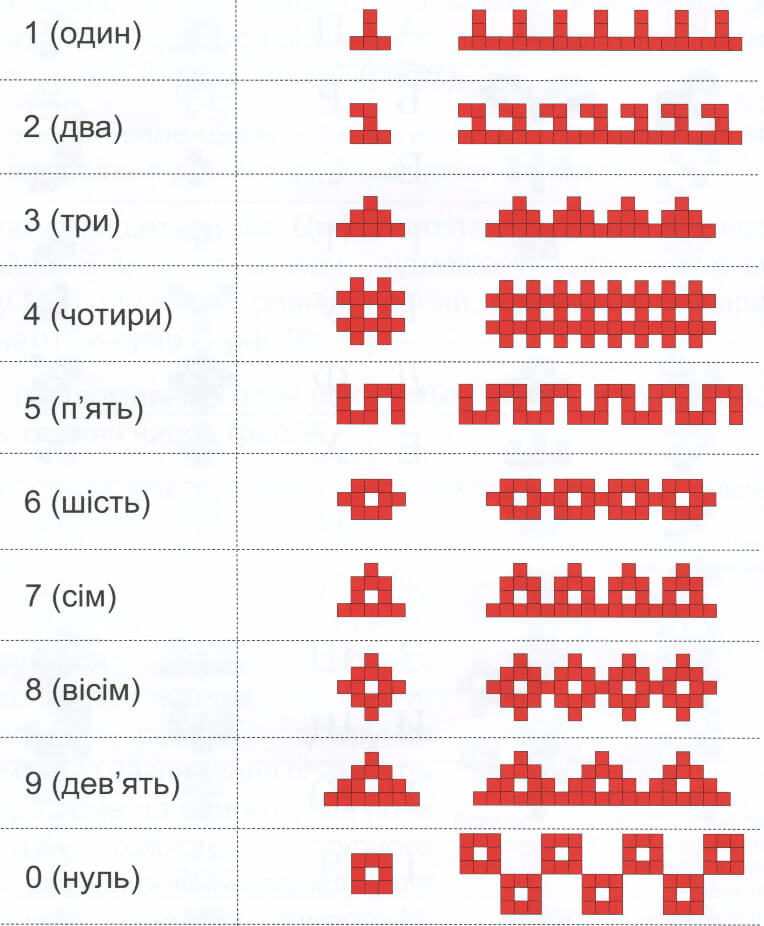

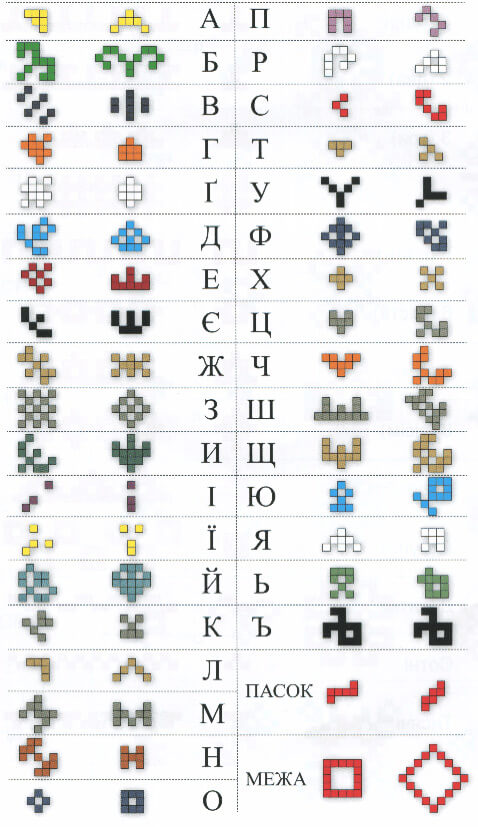

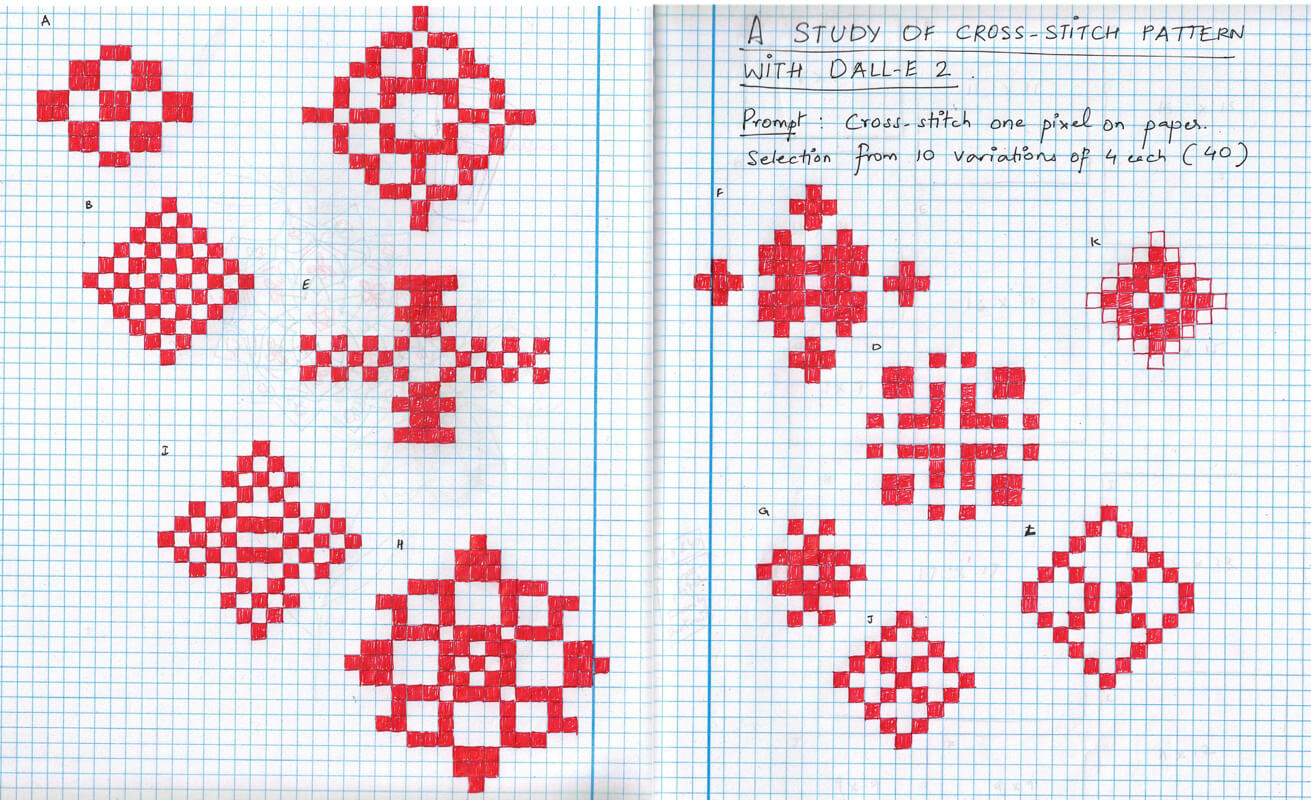

il. 1. Twelve unit variations of cross-stitch generated by the author using a DALL-E prompt: Cross-stitch one pixel on paper.

il. 2. A visual study of DALL-E’s cross-stitch image variations on a grid paper, referring to them as ‘Family Resemblances’ because of their overlapping visual features.

BACKGROUND

As a design researcher operating in data-driven contexts, I have been carefully following recent AI trends. New AI tools such as “DALL-E”, “Midjourney”, and “Stable Diffusion” flooded my Twitter timeline with intricate, grandiose, and at times arresting images accompanying them. Simply put, DALL-E is a computer algorithm trained to ‘see’ like humans and ‘read’ patterns from existing images. It, in turn, generates images by analysing and matching those patterns against new text inputs. Today, tools like DALL-E are publicly available for exploring AI’s potential, no matter one’s level of AI expertise or technical literacy. Many AI models support the creative processes of artists and designers, wherein the artist must express their thoughts in natural language prompts, which the AI translates into image variations (four images per text prompt). However, how does one understand these images and differentiate between the image variations? Is it a matter of creative interpretation, or is there more to it – a way to ‘read’ the generated images, knowing that real datasets drive them?

In his newsletter ‘How to Read an AI Image’3, Eryk Salvaggio writes that AI outputs are not pictures but infographics of a dataset. He explains how AI images are nothing more than data patterns inscribed into pictures – pictures that tell stories about datasets and the human decisions behind them. However, it is easier said than done because no single method or key exists to unlock AI images, telling us how to associate the generated images with their datasets. Large-scale datasets are vast image collections that companies scrape from the open web without consent and copyright restrictions4. Even if some datasets carry open-source licenses, their data models and architecture are closed off to public. This is why data scholars and media researchers everywhere call for critical methods to understand and explore how AI tools embed particular ways of seeing (patterns), especially as they are collected, analysed, and deployed via undisclosed categories, ideas, and vocabularies5.

For this particular project, I followed the method of Critical Making6, which incorporates material modes of engagement with technology to open up social and cultural reflection. The approach aligns with do-it-yourself, open-source movements, and critical technical practice7, which utilises critical literature to question the tactical components of crafting and making at the core of any technology. In her book Critical Fabulations8, Daniela Rosner draws from feminist technoscience discourses to suggest how adopting historical craft perspectives can help rework prevailing computing narratives around scale and innovation. Critical Making provides a suitable framework for adopting a crafter’s perspective to creatively interrogate an AI system and interpret its underlying processes by applying philosophical and sociological lenses such as Wittgenstein’s.

FAMILY RESEMBLANCES: CROSS-STITCH & DALL-E

According to Wittgenstein, the idea behind Family Resemblances entails the cultural concepts we ascribe to things and group into categories that do not always have one defining feature but a series of overlapping features. He provides the example of ‘games’ wherein what constitutes a game, i.e., whether it has rules, whether it is for fun or play, and if it entails winning and losing, is decided based on overlapping features and their social and cultural contexts9. Similarly, wide varieties of cross-stitch exist when one considers cross-stitch an embroidery category (e.g., full cross, double cross, mini cross). Cross-stitch varies culturally, carrying different names and styles, and it incorporates other historical embroidery forms such as needlepoint and blackwork. Nowadays, digital art forms like ‘pixel art’ characterise cross-stitch and define its computational features. Acknowledging multiple features and their (co-)relations makes it possible to come to a common understanding of what is and is not cross-stitch. Arguably, on some level, this is similar to what DALL-E is doing when tasked to generate image variations based on natural language text prompts via a shared concept or category. DALL-E’s model stitches together metadata and images from its large-scale datasets that contain cross-stitch patterns across history and culture into visual resemblances of what we want to see. However, the real question is whether DALL-E can reverse engineer those visual resemblances, showing us how it constructed them, tracing back to categorical features of cross-stitch and their socio-cultural and historical references. Why is this question vital, one might ask?

Our human history provides countless examples of visual craft languages represented in non-linear, coded, patterned, and symbolic formats, i.e., beyond linear rule-based scripts such as Latin or Devanagiri10. Within their socio-cultural contexts, crafted visual patterns are instantly recognisable and distinguishable in that those who created the data (patterns) cared enough for their encoded algorithms to exist in an open and accessible manner, supporting the creation of emergent styles and meanings11. Consider, for example, cornrow hairbraiding styles that have evolved over the years. This centuries-old African vernacular tradition embodies algorithmic fractal patterns while revealing a person’s age, whether they are married or not, their social status and religion12. Today’s cornrow braiding styles instead tell stories about hip-hop culture and AfroFuturism. Similarly, Kolam, originating in Tamil Nadu, operates as a computational, open-source heritage craft passed down through generations and practised by millions while exemplifying Tamil culture’s embodied, emotional, and intellectual facets13. As AI models become increasingly capable of advanced forms of visual pattern recognition or simply ‘seeing’, our goal is to examine not only how computational capacities give rise to new creative expressions but also how we uphold values and beliefs that closely relate to cultural and embodied ways of thinking, knowing, doing, and interpreting in an open, visible, and understandable manner14.

If this is the goal, then to what extent can our interactions with DALL-E facilitate an open and accessible account of the historical and cultural meanings behind cross-stitch? Whose references do we build on? Who is behind the cross-stitch images that feed its dataset? Do they consent to how DALL-E’s AI model treats their cross-stitch patterns? With how DALL-E’s model currently works, we may never be able to answer these questions. Nevertheless, could we at least partially ‘read’ DALL-E’s images in easily accessible grammar, like the ease with which we read the scripted language or distinguish texts from one another? If we consider cross-stitching a ‘language’ with its coded patterns and grammar, could one imagine alternative ways of ‘reading’ DALL-E’s cross-stitch variations?

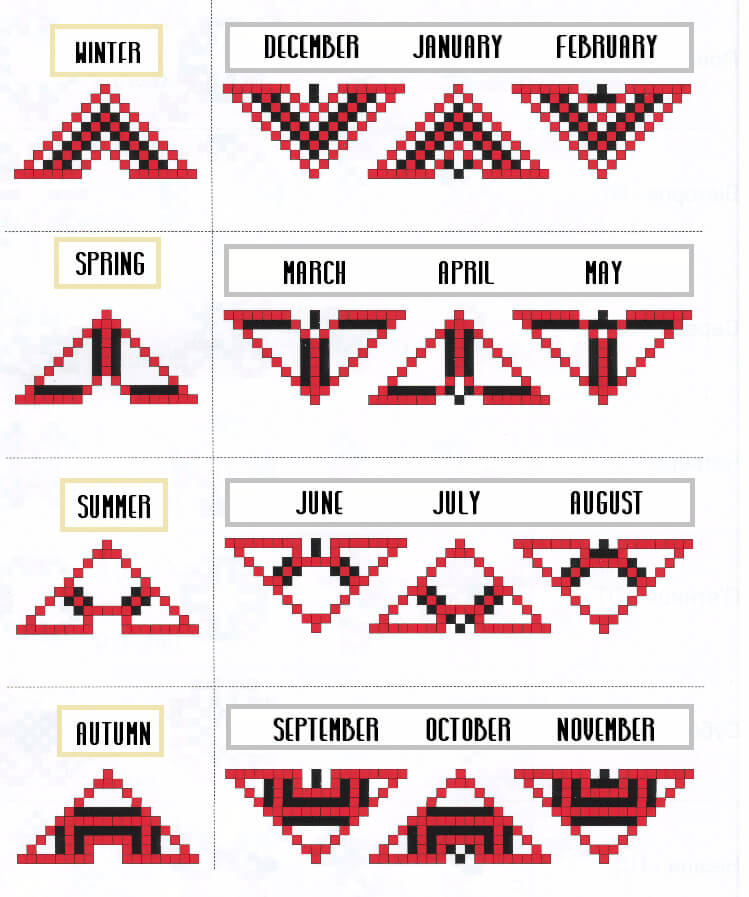

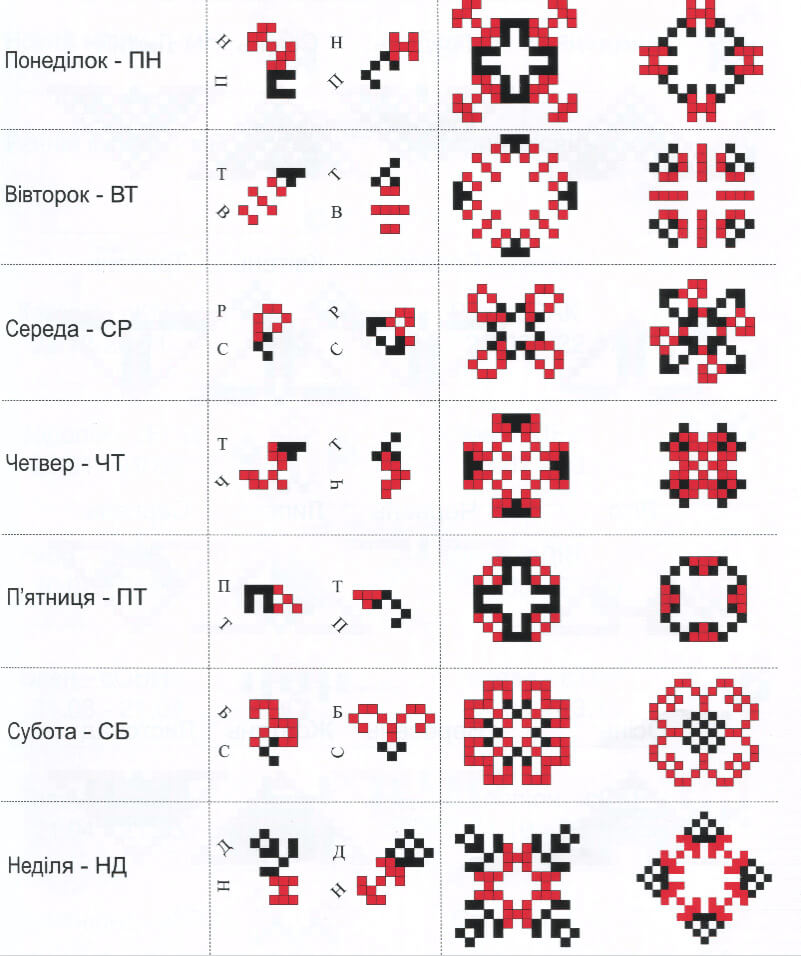

DECODING DALL-E WITH PYSANKY CODES

After searching for keyword combinations such as ‘cross-stitch’ and ‘codes’, I noticed visual similarities between DALL-E’s cross-stitch images and Ukrainian embroidery codes, based on a 2008 book authored by Volodymyr Pidhirniak titled “Text Embroidery – Brodivske Lettering”15. This historic Slavic embroidery style encodes cross-stitch with aesthetic and decorative meanings and has done so for many generations. Their cross-stitch variations are symbolic and religious and extend to ritualistic forms of record keeping of family names, numbers, days of the week, phases of the moon, months, seasons and astrological signs16.

il. 3–6. Images illustrating how numbers, weeks, (Cyrillic) alphabets, and seasons are depicted in Ukrainian encrypted embroidery. Images sourced with permission from the original copyright holder – Admin at https://ukrainian-recipes.com/encrypted-embroidery-how-to-depict-words-and-numbers-in-ornaments.html

Pysanky is the name given to the art form of encoding these cross-stitch-like symbols on Easter eggs (instead of fabric) using wax resist and natural dyes17. Pysanky translates the visual structure of the Cyrillic alphabet into stylised cross-stitch units (Brodivske lettering) that are non-linear, patterned axially from the centre, and, most importantly, readable! However, the actual origins or history behind this writing system are unknown.

“Encryption [with embroidery] looks like a modern QR code: each symbol hides a letter and a number that together create a unique charm pattern. Thereby, anyone can use such an embroidered alphabet and convey a message via ornaments. And all who learn how to use such an alphabet, will gain a new level of knowledge of the Ukrainian language.” – Admin (ukranian-recipes.com, n.d.)19

il. 7. How to “write” the words MAMA (mother) and TATO (father) in Brodivske embroidery lettering. Images sourced with permission from the original copyright holder – Admin at https://ukrainian-recipes.com/encrypted-embroidery-how-to-depict-words-and-numbers-in-ornaments.html

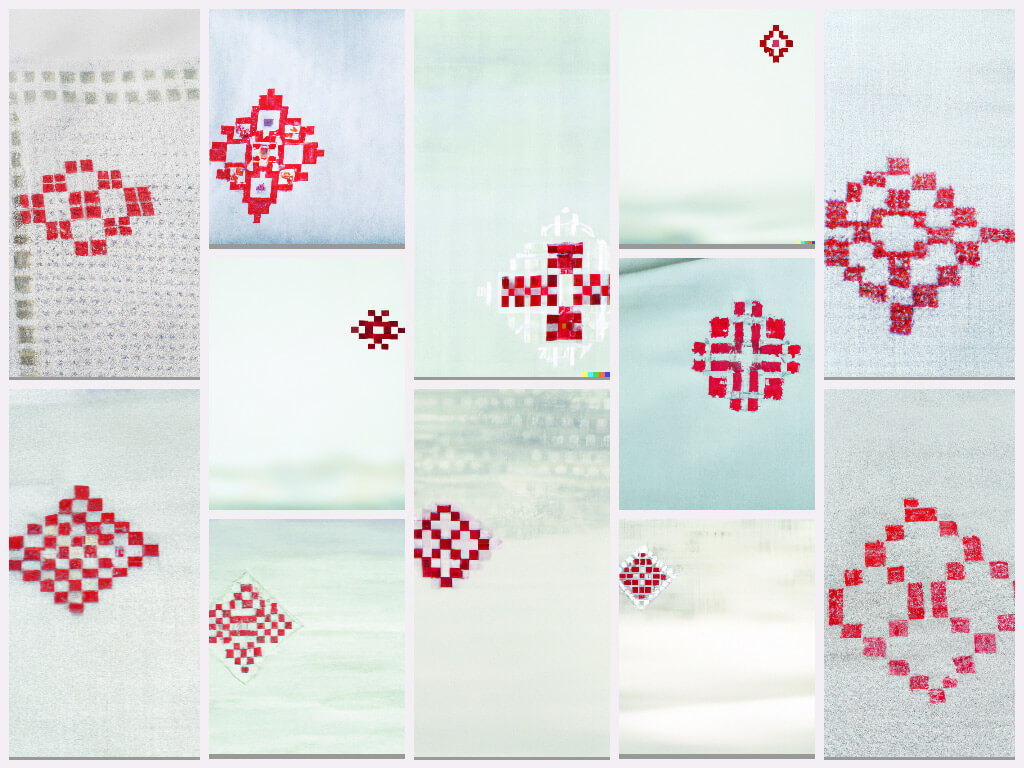

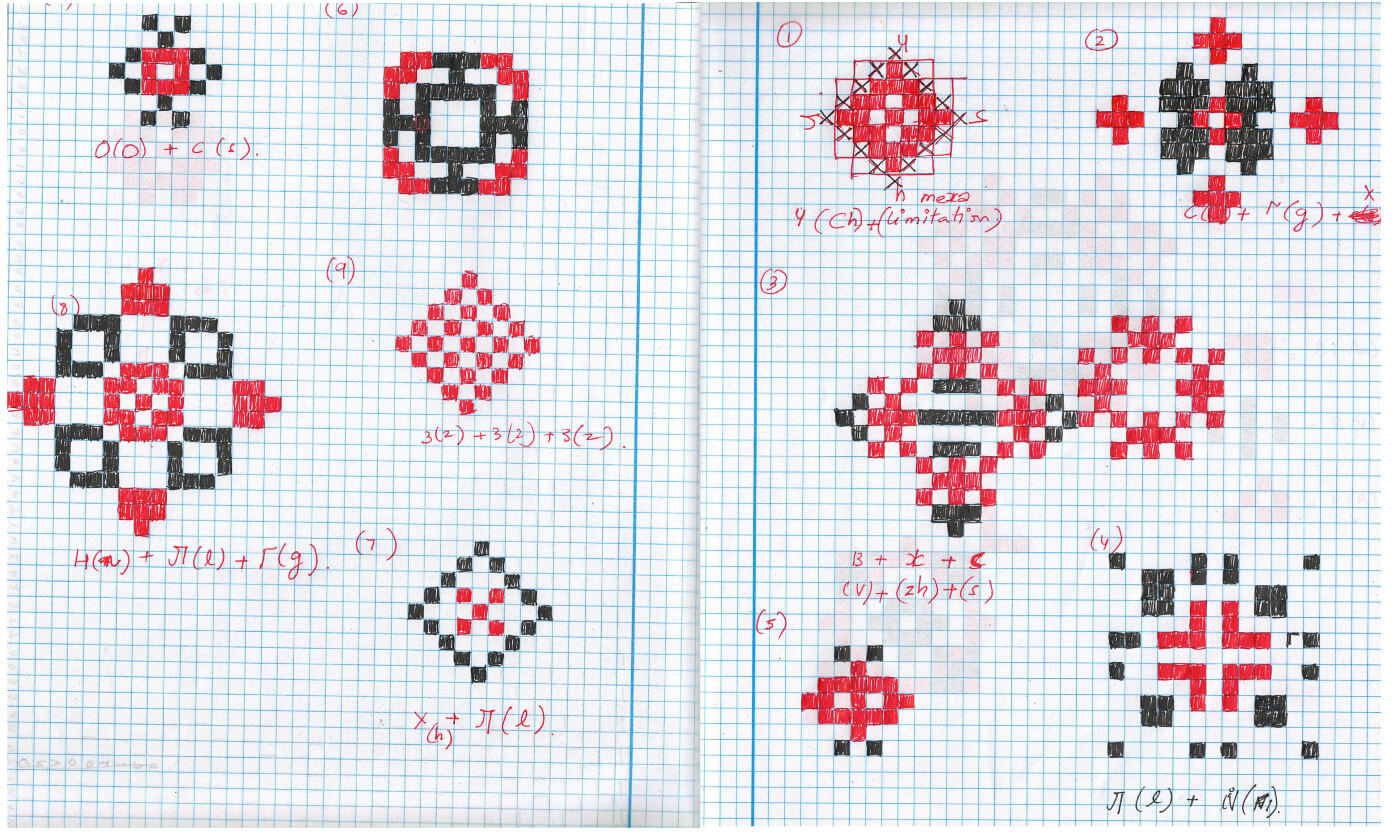

As an experiment, I wanted to see if I could decipher DALL-E’s cross-stitch image variations through historical and culturally-encoded Pysanky. I put on my hacker hat and first attempted to decode DALL-E’s cross-stitch units into the Cyrillic alphabet. I interpreted some Cyrillic alphabet with the help of a translation service, although it did not make sense when I put the letters together. In the process, I hoped I discovered a hidden “language game” between DALL-E and Pysanky, but I ended up with gibberish instead. Could “н л г” be someone’s initials, an abbreviation, perhaps?

il. 8. The author’s attempt at decoding DALL-E’s cross-stitch unit variations into Cyrillic alphabets using Pysanky embroidery codes.

CRAFTSPEOPLE AS CREATIVE AGENTS FOR AI

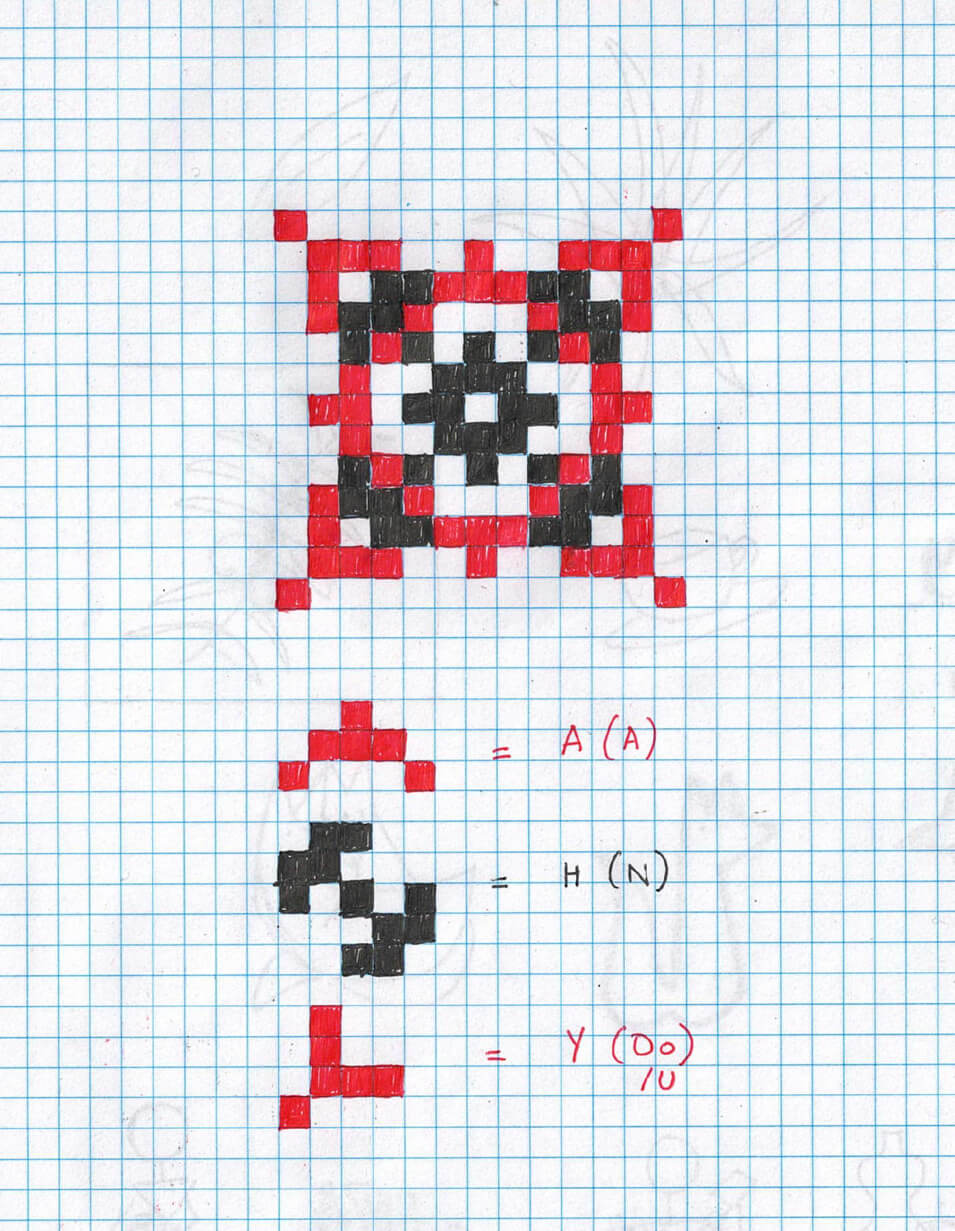

As it turns out, so much of our engagement with new AI tools is about making sense of things that do not readily make sense. We know that generating a meaningful image output using DALL-E requires tweaking the text prompt multiple times until the text stops making literal sense. If the literal meanings of the text prompt no longer make sense, then another hidden translation process takes place in ways we do not understand. So, we keep poking at it, playing a slot machine-like language game until our brains run dry20. However, asking how these processes could make sense and finding meaning is crucial to our relationship when interacting with these tools. Undertaking a Critical Making approach led me to encounter a new script, Cyrillic, which was only possible by my theorisation around DALL-E’s visual cross-stitch resemblance with Pyansky patterns. In doing so, I acquired a new appreciation of cross-stitch by understanding its ‘readable’ features. I even learned to write my shortened name (ANU — Ану) in Pysanky. I first tried some pattern variations on grid paper before narrowing down on a pattern I liked. I then reproduced the pattern using traditional and new fabrication processes: I cross-stitched my Pysanky name on a denim blouse by hand and then made a 3D-printed coaster of the same pattern.

il. 9. The author’s shortened name “written” in Brodivske Pysanky code pattern

Hybrid formats of creative expression, reappropriated from a historical and cultural craft like Pysanky, allow us to slow down and reflect on our relationships with AI tools – tools that fall short of broader capacities for meaning-making and story-telling that historical crafts provide via open and easy-to-understand visual and cultural algorithms. As we are predisposed to ignore crafts’ life-sustaining efforts and go after AI for newness, it becomes apparent that AI is quite good at recycling its datasets to show what appears like crafted visual languages devoid of social or cultural embodiment. Embracing the nuances of crafted art forms, as presented in this article, exemplifies the non-linear, embodied, diffractive ways of reading, interpreting, and understanding the world while questioning what AI tools can do and the extent to which craftspeople have a say in what AI tools should be doing instead. I contend that AI does not produce newness but rather ‘newly’ suggests how craftspeople have always been creative agents for shaping the future of culturally and visually-informed algorithmic systems. With open-source AI movements steadily advancing, I hope the focus shifts from scaling and efficiency to the innovative possibilities for craft communities to reappropriate AI through interactive visual styles and patterns capable of supporting their communities’ life-sustaining needs and practices.